How do I recover from being whitewashed?

Repairing a childhood of self-loathing + a message to all the brown artists

Note: I updated some of this newsletter after I recorded the voiceover. The most updated version can be read here but if you’d rather listen to me, you’ll still understand the point of my piece. Unpacking this topic was hard and healing for me. Thanks for reading or listening. Peace and love.

This story has no ending.

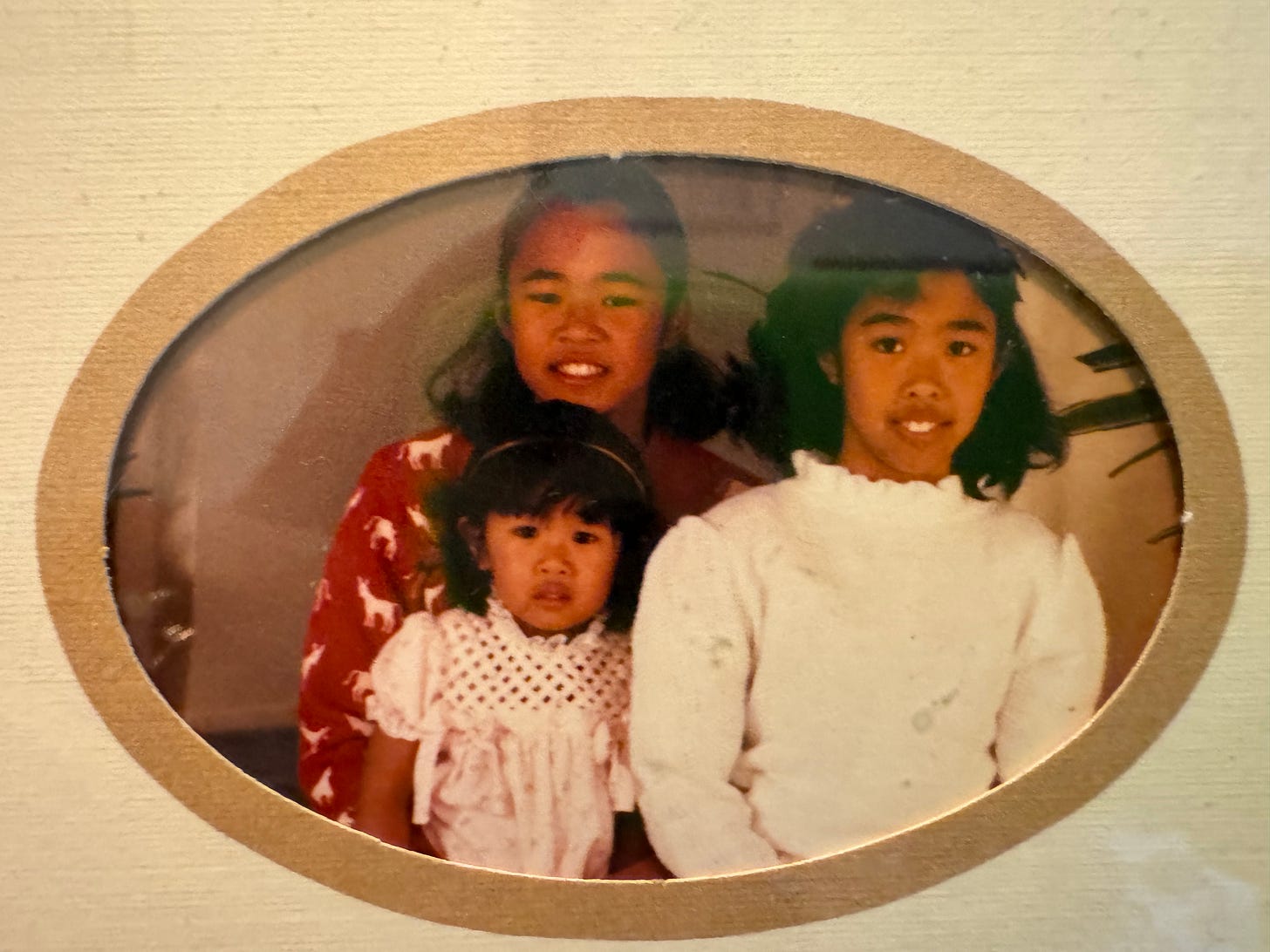

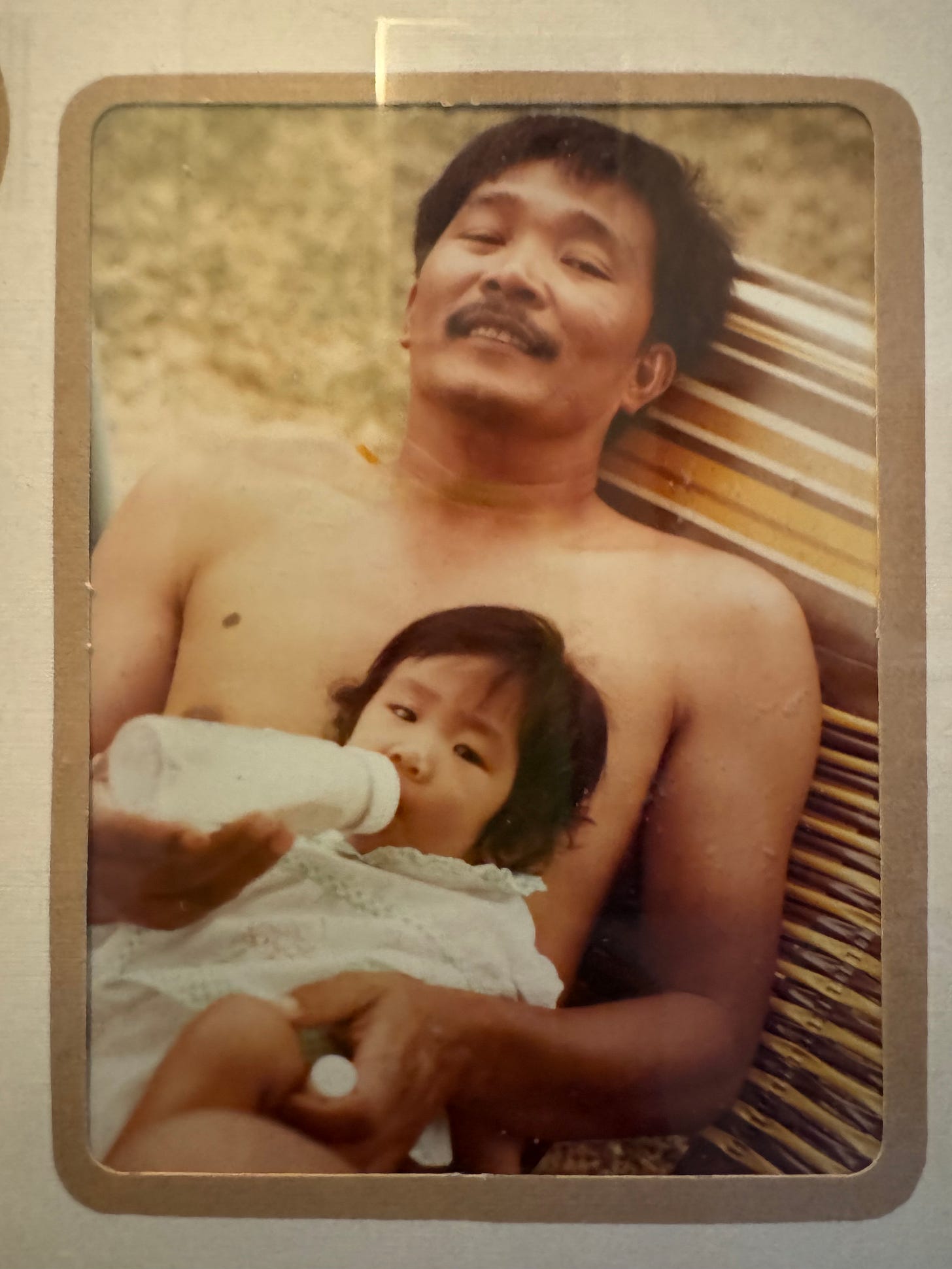

It has a beginning, which involved me as a little girl, wishing I could change my deep-brown skin and dark slanted eyes.

We are now in the middle of the the story and it involves me as a mother, raising biracial children. My daughter and I recently talked about race, segregation, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and I left her bedroom with sadness. While I didn’t share it with her, the discussion brought up memories of my own childhood, my relationship with my brownness and my own internalized racism.

Rubbing it in

Before I tell you my beginnings, I’ll take you back to 2010 when I went to the Philippines with my mom. The last time I was there, age 6, I felt like a star, surrounded by cousins fighting over who gets to play with me, the girl from America.

When I went back to the Philippines as an adult, I found myself surrounded by something else. I was bombarded with billboards, the glaring thing to stare at in Manila’s insane traffic. There were ads everywhere for face whitening creams. At my aunt and uncle’s house, it was there too, on TV commercials; I watched beautiful light skinned Filipino women with flawless faces, gently touching their skin, alluding that, you too, can be this beautiful with their skin whitening cream. When I went to the mall with my cousins, I could not avoid the cosmetics section subliminally telling shoppers that whatever melanin they were born with, it can be fixed with this blob of goop you can spread on the largest organ of your body. You can be whiter and, therefore, worthy.

I went to the Philippines shortly after my honeymoon, when I was tanned, felt beautiful, and in love. But in the two weeks I was on my ancestors’ soil, I felt ugly and unwanted — a feeling I hadn’t revisited since I was a child.

The beginning

I was born in the Los Angeles-area in 1983. My parents immigrated to the US in the late 1960s, thanks to my dad’s service in the US Navy. As I grew up, my town became more racially diverse. My neighborhood was once a pig farm and horse community, predominately white, and then eventually became more densely populated with Asian and Hispanic families. In 2001 when I graduated high school almost half of all Filipino Americans in the U.S. lived in California.

The people around me looked increasingly like myself but I leaned into what I consumed in pop culture.

I was a classic 90s kid.

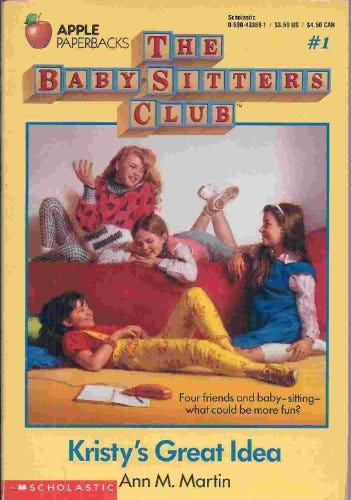

I lost myself in TV shows, The Brady Bunch, Full House, 90210, Friends, — nearly all white casts. Same with movies I loved, like Kevin Smith films, 10 Things I Hate About You, Clueless.

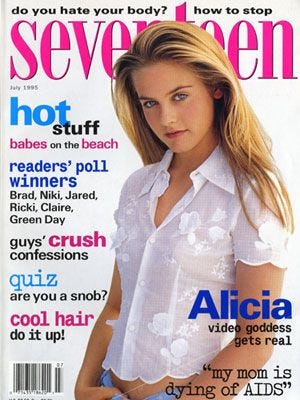

I pored through magazines on the shelves at the grocery store, Teen, CosmoGirl, YM, and Seventeen. Every single page, every single cover, in my memory, were filled with mostly white women.

I almost exclusively listened to ska, punk, rock, alternative rock, No Doubt, Nirvana, The Cranberries, Sublime, 311, Veruca Salt, Red Hot Chili Peppers. All white musicians.

I read white, I watched white, I listened to white. As difficult and embarrassing as it is to write this now, I admit — I wanted to be white.

I did consume popular culture that had more diversity, racially, but it was lacking. I watched The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, A Different World, Family Matters, and other shows and movies with black and latino characters but, we were just scratching the surface. Back then, besides a sprinkle of Joy Luck Club and All American Girl, or the 2-second part with the one Asian friend in Clueless, anyone close to who I identified with — the complicated and all encompassing word, “Asian” — was hard to find in pop culture. Depictions of Asian characters were still very much an “other” or model minority trope, or were akin to Long Duk Dong in Sixteen Candles (a movie I do still love). Portrayals of indigenous peoples as savage were still so prevalent in American storytelling (the dinner and human sacrifice scenes in Indiana Jones’ Temple of Doom come to mind because I recently watched it with my kids).

Meanwhile, in my own reality, I never felt I belonged anywhere, which I know is a common experience among many first-generation immigrant kids. I was not Filipino enough. For their own reasons, which I do not blame, my parents didn’t teach me and my sisters their native language so time spent with extended family or at other Filipino gatherings felt isolating.

We were certainly not white-like enough. In 2nd grade, after a weekend of playing in the sun, I arrived at school tanned. A girl in my class told me, with a tone of disgust, “you’re really dark.” I didn’t want to play outside anymore after that. I would look in the mirror and agonize over my “Chinese” eyes (my classmates would tell me), and I wished they were a different shape and a lighter color. I hated my “flat” face and my nose felt too round and pudgy.

I wished my parents didn’t have Filipino accents. I thought my house was gross because it smelled like the fishy foods my mom cooked, even though I loved eating them. I thought everything I came from was weird and I didn’t want to be weird. I wanted to be white.

I found belonging in a place where I felt comfortably foreign. I desperately wanted to be liked and loved and I felt the way to do that was to assimilate to my white-centric American culture and shove away where my ancestors came from.

The light-skinned obsessed

Like the cousins flocking to the girl from America, we know the fascination with lighter skin is related to a weird and complicated relationship with the West. I’m sure it was also rooted from being colonized by Spaniards in the 1600s. It isn’t just in the Philippines; many places equate darker skin with labor outdoors, a sign of lower economic status and poverty.

Though hard to admit, I witnessed anti-dark sentiments in my family. What we were taught comes from generations of conversations, which then infiltrated the dinner time talk in my childhood home. I remember my parents mentioned Igorot people, the indigenous people who lived in the mountains of Northern Luzon, Philippines. After a quick google search, “cultural elements common to the Igorot peoples as a whole include metalworking in iron and brass, weaving, and animal sacrifice.” I don’t recall any of these descriptors but I do remember we talked about how they were dark, “black,” and therefore ugly. Forms of racism are everywhere and my family unknowingly spread it in our home, leading me to wonder how much I unknowingly do it in mine.

How do I reckon with my own internalized racism?

A common therapy exercise is relevant here: Name It To Tame It.

So here goes.

I was whitewashed. Maybe I still am. But, unlike the skin whitening creams I was so offended by, I’ve decided there’s nothing to be fixed. Not my skin color, not my former self-loathing as a child, not my former feelings of my racial background, not even the lack of diversity in the books, art and pop culture of my childhood. I’m here today, a proud first-generation Filipino American and this pride is a culmination of everything I experienced and consumed until now.

I am not trying to change the past, it is part of me and I do not need to deny or condemn how I felt.

Let me be clear. This isn’t an anti-white piece. It’s far from it.

I’m married to a white man. The majority of my friends are white. I have two children, who are half white.

Perhaps the answer to my question in the headline of this newsletter, “how do I recover from being whitewashed?” is aimed toward forgiveness. I recover by forgiving myself for simply wanting to fit in. I now hold a responsibility to model kindness and curiosity with my mixed race children. Neither of them are “white passing” and they have many of my physical features. I hope they find more beauty in their skin and where their ancestors are from — from both their father’s side and mine — with the help of us being mindful of what they consume.

50 Shades of (Brown)

I have heard the question, are we born color blind? Are children unaware of race? Studies say children are aware of race by age 5 or even younger. I’ve also heard the idea that maybe if we don’t bring up race, racism wouldn’t exist.

Personally, race is all I saw as a kid. I saw 50 shades of a white world and I was a brown girl trying desperately to be a part of it. I don’t wish to see a world without a discussion of race — it’s our roots and it’s the fabric of who we are. A denial of this discussion is a denial of our existence.

“Never trust anyone who says they do not see color. This means to them, you are invisible.” - Nayyirah Waheed (Poet)

So here we are, still very much in the middle of the story. I mentioned earlier my fear of unknowingly bringing forms of racism into my home. All I can do is continue to learn, and read, and be curious. I try to be purposeful about what my family and I read and watch — and also have discussions about them.

There’s the scary threat of banning books at schools so, in response, what if we bring more perspectives in to our own homes?

A message to brown artists

To all the first-generation, immigrant, brown and black writers, artists, and creators, please know the little girl in me wants to see your work.

I went to college in 2001, read more diverse literature than what was offered in my public schools, and it was the beginning of me loving myself. The Internet boomed and artists and creators of so many racial backgrounds started making it into the mainstream. Every article, every movie role, every artist I saw with a hint of a story similar to mine, gave me permission to accept more of myself.

We all want to belong.

I can’t say this enough. Representation matters. Writer

quoted Marian Wright Edelman in her piece on representation: “You can’t be what you can’t see.”In recent shows I’ve watched, like To All The Boys I Loved Before, I cried seeing the 3 sisters, all mixed races (like my kids) in lead roles. I devoured three seasons of Mindy Kaling’s teen high school show, Never Have I Ever. Leading actors played “normal” kids of today, with their race just a part of their complex characters. Thank you to Bretman Rock for being unapolagetically Filipino to his 18M+ followers. Thank you to Olivia Rodrigo to sharing her beautiful lyrics and music genius as a half-Filipino musician. Even racially diverse books and shows can still be problematic for accuracy or still continue stereotypes but I think the more mindful we are of what we watch, and read, then hold honest discussions about them, we can instill more compassion in this world.

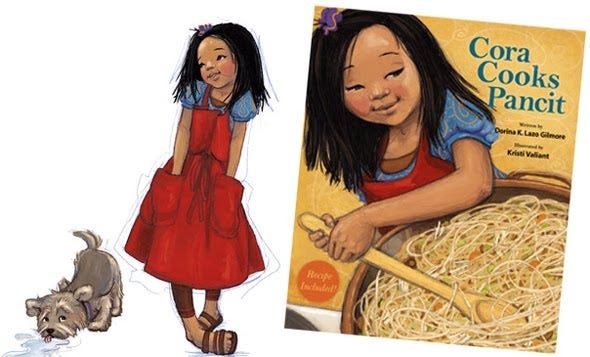

In my house, we make an effort to read all sorts of perspectives. Some of my favorite books are written by authors of various racial backgrounds. I’m proud of the stack of Filipino storybooks we keep on our shelves. Like I did as a kid, my children hear my mom’s stories of growing up in the Philippines. We cook Filipino dishes together and my daughter isn’t embarrassed to bring leftover chicken adobo for school lunch. I can’t help but think those storybooks gave her a sense of pride.

Don’t be afraid to put out your work, no matter how many followers, fans, subscribers you have. It’s scary and it’s vulnerable but we need to continue to see more people who look like us share their stories. Please know that a little brown girl from the 90s is rooting for you and seeks your work.

Substack Reads: Rising Writers

This is a play on Substack Reads — a curated list of Substack articles I enjoy. My version includes authors with smaller subscriber numbers (in the hundreds).

I made an exception for my list with

because she has 1K+ subscribers. Her piece this week explores the topic I touch on, having biracial kids and she goes on further to talk about having a “white passing” child. has been collecting an Asian author booklist, which she shared with me here! Her story examines a relatable experience many immigrant kids have - distinguishing who they are and removing it from what they accomplish. wrote a piece on feminism that is honest and approachable and I think everyone should read it. It’s about a sibling relationship, it’s about checking in with our loved ones even though we may have nothing in common, it’s about taking action and finding ourselves with a little more empathy. Read the comments in her piece, too.I just started following

because I haven’t been reading enough about the female Muslim experience and feel the need to understand it more. She writes in a very approachable and honest way. It’s not preachy, feels authentically her and she shares viewpoints, such as this: “I hope it goes without saying, but just in case: I don’t believe women should be forced to wear a hijab, or to take it off. Kimia and I discussed the fact that, in her native Iran, women have to wear it, which I take as a violation of their freedoms.” wrote a piece for us to think about after he watched a harrowing video of a boy in his native Colombia, which had him thinking about the experience of many children around the world. Loved the end, where he shares his promise to his nephew in response.

This was an extremely touching post. I am a multiracial person and grew up with a black parent always telling me he wanted hair like mine (my hair is straight), skin like mine, and more 'white' features like mine. It made me really uncomfortable with the things that he considered black about my features. That sort of internalized racism gets passed down and it's confusing. My dad always said because I'm racially ambiguous I can fit in anywhere, but in my experience I don't feel like I fit in anywhere at all.

While I don't share the experience of having immigrant family, I can share that feeling of a lack of belonging. Thanks for sharing your experience and what I see as generational healing 🖤

This piece is brilliant, Stephanie. My son is half-Burmese and since he was about four, has always commented on who in his class is black, brown and white. His mum is white and his dad is brown: of course he noticed it. “So and so is brown, like me.” When he was six, he asked me why no one in LOTR is brown. I had never even thought about it. He is obsessed with Hamilton (we watch the Broadway original on Disney+) and I’m taking him to see it onstage in London. He asked me “will it be the same Actors” and I said no and he said “ok, but will they be brown?” They will. I try so hard to teach him how beautiful his skin is and how amazing his Burmese heritage is and how lucky he is not to get sunburned like me. I worry constantly that an idle remark at school or an unconscious failing by me will undo it all. Also - what you said about families mirroring it back resonated. When I lived in Burma, talk in Burmese is often peppered with frank discussion of exact skin tone, praising “a phyu” (white) and shaming “a mey” (dark) or anyone who looks “kala” (a really derogatory word for Muslims from western Burma near Bangladesh). That racism only happens in Burmese language but it is loud, shameless and ever-present. Thank you for this wonderful piece that made me think a lot. ❤️