When I speak with my race's accent, is it hurtful?

is it poking fun or is it just fun? + an invitation to be honest with ourselves, our relationship with race and language, and why we act and think the way we do

A few weeks ago I wrote about my self loathing as a child and internalized racism. It opened up a can of worms. For me.

Maybe for you, too. But this is about my own experience. Where I crack open parts of myself I’ve left shut for a long time.

When I wrote about being “whitewashed,” I omitted chunks, large meaty chunks of thoughts, questions, and ideas related to race. I had so much to say and not enough time to process it. Today, we process one of those chunks.

I keep coming back to the question:

Is it racist if I speak in a Filipino accent?

Specifically, when I’m speaking in (US) English and copy the Filipino accent.

Before I get any further, I’m going to spoil the ending for you. I have no answer. Is there an answer? Maybe, maybe not. Or maybe not yet. And maybe there’s an answer for you because our relationship with our own race(s) and language(s) are so personal. Feel free to use today’s newsletter as an invitation to do the same for yourself, your family, and be kind with what you might realize.

This is an uncomfortable topic. It can be divisive. I’m still actively working through it. I observe my thoughts, beliefs, intentions, and actions. This exercise is only meaningful if I take the time to be open minded. Not jump to conclusions.

In conversations with my friends and family, we’re all quick to defend my use of the accent. It’s part of my verbal storytelling. It can be light humor for all of us. It paints my family in an endearing way. Plus, I always figured, since I’m Filipino, I can copy my heritage’s accent, right?

I guess now I’m not so sure.

In telling stories to my friends and family, typically about my mom and dad, I’ll copy the quirks in how my parents say their words. For example, my name is “e-Step-anie.” Filipinos tend to switch the pronunciation of Ps and Fs. Words with a V are pronounced with a B. Sometimes the letter S is pronounced with a ‘sh’ sound. The intonation for words are jumbled and they tend to pronounce every single syllable. Not sure why, but Filipinos tend to say Traders Joe rather than Trader Joe’s. We watch videos on “You-Chube.” We eat “Prench Pries” with our hamburgers.1

See? It’s all simple harmless fun. And comedians do it, too. Entire audiences laugh along with them. Including me. So it’s ok, right?!

But is it?

I recently went to a local Chinese food restaurant with my kids, cracked open a fortune cookie, ate it, and unfolded the tiny piece of paper. It read “Confucious say…” and I stopped. I didn’t want to say it out loud to my kids. I immediately went into question mode. Does the “confucious say” statement perpetuate the “broken” English stereotype? Is it a rude imitation of the Chinese accent?

Do you remember the question I keep coming back to? I originally wrote it like this:

“Is it racist if I mimic the accent?” I paused and analyzed. Is that word sincere? Or is a more appropriate word mocking?

How do we know the difference?

My mom came over for a visit earlier this week.

We heard this explanation many times growing up when my parents had to justify to others (especially to other Filipinos) why they did not teach us their native language. Their dialect, Ilocano is only used in a few provinces that my parents are from in the Philippines. They didn’t want to teach us a language that wasn’t widely spoken. For those of you who don’t know, the Philippines has more than 175 languages and dialects and its national language, the one most spoken throughout the island nation, is called Tagalog. My mom did not speak Tagalog well and, therefore, did not want to teach us a language she didn’t speak fluently. (My mom told me my dad would nudge her to stop talking when she attempted to speak her “broken” Tagolog.)

I hadn’t heard her say the following line in a long time until she mentioned it during her visit this week. My parents feared we’d look like “second class citizens” in America so English was the first and only language my sisters and I ever learned.

I am saddened to think that my mom believed we’d be perceived as lower class by sounding like her but it was the 80s and 90s. Could you blame my parents for having this fear in our American culture at the time?

Where was the belief stemmed from? This is part of the tricky balance in assimilating to being American as an immigrant. My dad (who passed away in 2015) was the most patriotic man I knew. He served in the US Navy for 20 years, fought in the Vietnam War and loved this land that offered opportunities for him and his family. He was a staunch supporter of making sure his girls were respected in this country.

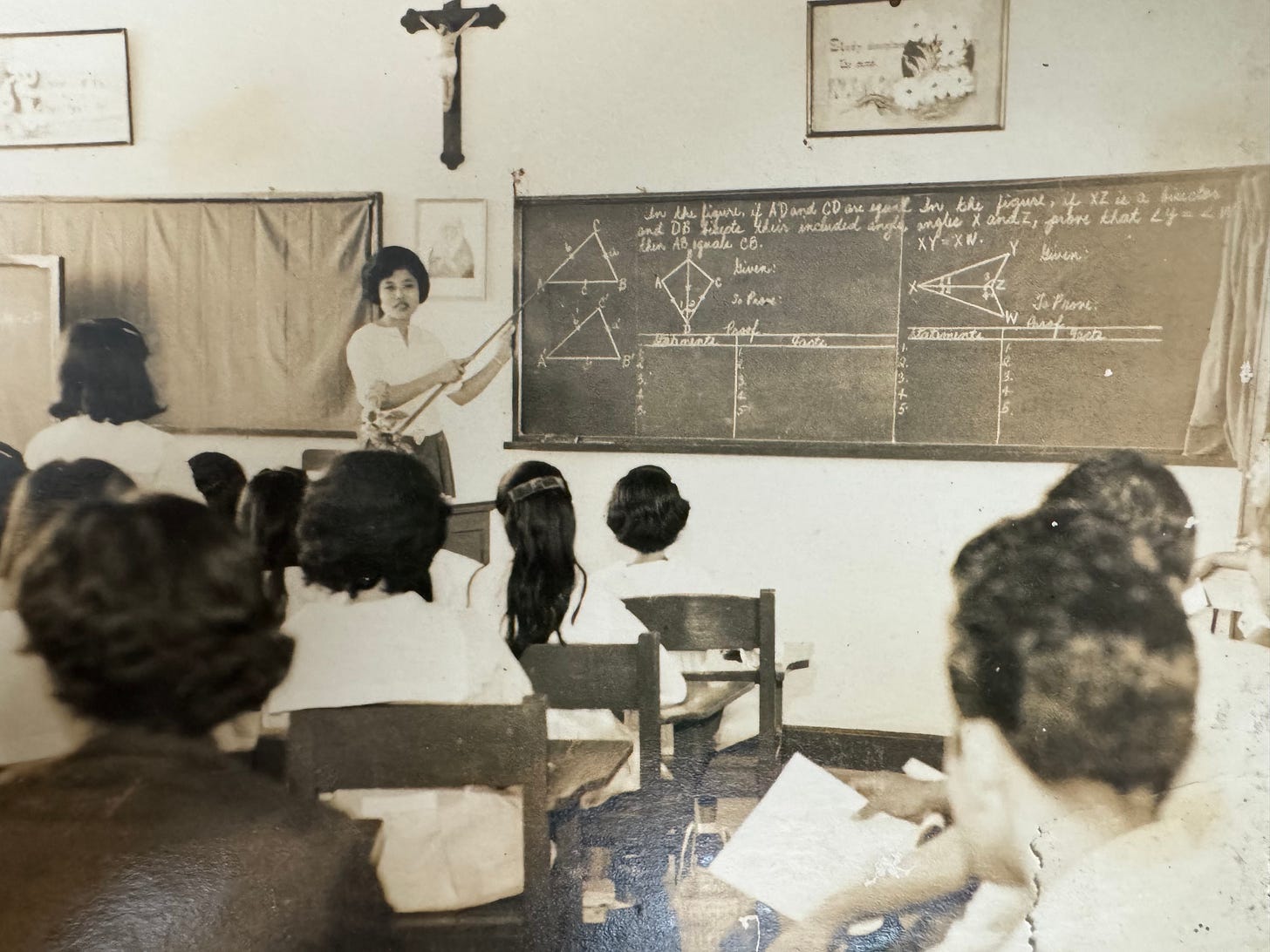

This pull toward a westernized, English-speaking culture also came from long ago, on my ancestor’s soil. One example came from my mom’s childhood. At the school she went to in the Philippines, English was the only language that was allowed to be spoken. If she was caught speaking her native tongue or any other language except English, she was given a fine to pay on top of her tuition. What does that do to one’s psyche about their relationship with their native language?

Although my mom has spent the majority of her life speaking English, she has always had a strong Filipino accent.

My mom told me that when she first moved to the US in her 20s, she didn’t answer the phone because she was afraid the person on the other end of the line wouldn’t understand her. My mom had come here completely fluent in English but the fear stood strong in her accent to keep her silent.

Knowing this, is it fair for me to copy an accent that my mom was so afraid to speak out loud? Or is me using the accent a way to normalize it?

I have often felt “more American” because I only knew English.

And because I couldn’t speak any language from the Philippines, I never felt Filipino enough. So I leaned into the idea that I was the upstanding citizen my parents wanted me to be. After all, the only natural accent I did and do have is the California girl accent. It’s filled with “likes” as filler words and the classic “California vowel” shift. “DUUUde. That was FREAKing awesome.”

Growing up, I noticed the accent was an invisible divide. It became apparent to me when I would meet kids who had strong Filipino accents. It was the elephant in the room; we spoke the same language but that accent bridged us apart. Was that kid feeling not American enough similar to how I never felt Filipino enough? I imagine that the other kid’s experience was difficult in so many different ways.

One of my good childhood friends moved here from the Philippines when she was 11. She came here speaking perfect English and with a Filipino accent. I remember feeling relieved I didn’t have an accent like her. Gosh, that makes me feel like shit to think I thought that way. Why is that? And I’m sad to admit it.

Was this my parent’s belief passed down to me? If I had their accent, would I be taken less seriously? Would I be perceived as less than?

Hearing my mom’s accent is home for me.

It’s comfort. It is, after all, my mom’s voice.

Yet, when I was a child, I was embarrassed about it. Felt shame. At some point during my childhood, my mom took lessons on how to thin out her accent. I remember feeling excited for the outcome. This meant my mom would finally sound more like the other moms at my school. One step to being “normal.”

It obviously didn’t work. After the class, my mom recorded our home’s outgoing message on our answering machine, “You hab reached e-six two six…” It sounded thicker than ever. And I was bummed. Now, I’m bummed that I actually felt that way.

During my mom’s visit this week, we read a book I got for my kids, called “When Lola Speaks” written by Ren Reyes Dela Cruz. The first two pages lit me up with joy. I welcomed the book’s themes of accent and language and I was filled with resonance. The story began eloquently showing how accent can be innocently perceived to a child. Why does grandma say “such funny words?” The very cute and relatable book goes on to talk about why grandma says the certain words she says, infuses Tagalog in the story, and shows the bond between grandma and her grandkid.

This book prompted me to finally ask my mom if it offended her that I copied her accent.

She said no.

Honestly, I thought I’d be done with this internal debate on the accent when she gave me her answer. Essentially, I could be free from this contemplation. But this evaluation, for me, is still not over. Remember, I told you, I have no answer?

I don’t know at what point I started using the accent with my friends.

It made storytelling more interesting. It’s an act of endearment. Maybe it’s a weird way to connect to our “people.” At home, my sisters and I would think about the funny things our parents said in English. To this day, in my head, I still say words my mom and dad said in their accent (like hippopotamus and Seattle). My sister had a coworker who called in sick and we still giggle about the voicemail she left her, saying she took “Roo-bee-too-sin” to keep her symptoms at bay. (That’s Robitussin.)

When I speak in the accent, do I embody the stereotype that comes with it? What’s the stereotype I’m perpetuating? I don’t have an answer and now it makes me pause before I speak. Is it hurtful? It depends on the audience. It depends on my intent. It depends on so many factors.

Could speaking in the accent be a way for me to have a cultural connection because I do not know my ancestor’s language?

Does it make me feel more connected to my family, to my heritage? I hardly have any Filipino influences around me, geographically. What if I use it to reminisce something my parents said? Can the accent bring me closer to my memories of them?

This made me wonder, what is my intent when I copy another race’s accent? When I mimic the British accent, I think of pompous personalities, of someone who is higher class. When I mimic a US Southern accent, I admit, the drawl brings me the idea of an unsophisticated rural person. When I think of a Boston accent, I think of blue collar folks, who weather the harsher colder streets. Oh. And I also think of Ben Affleck and Dunkin Donuts.

I know, some of these thoughts I have are unfair. Sweeping generalizations about any group of people are unfair.

Like I told you. I have no answer. All this has done has made me more aware and filled me with more questions. Is me saying the accent out loud making the people who have the accent feel silenced? I don’t know.

I’ll leave you with this.

I think of three comedians who’ve copied the Filipino accent on stage, one who is Filipino, Jo Koy, and two others who are not and talk about their Filipino friends, Anjelah Johnson and Russell Peters. I enjoyed all of these bits. They made me feel seen. I was dying for representation as a kid. Acknowledgement of my culture! But I do know this could be offensive to others and I understand that feeling too.

It’s important to note that there is no one Filipino accent. As you can imagine, with 100+ dialects in the Philippines, each region has their own way of speaking and intonation.

You've given me so much to think about with this one. When I think about my own family, we do joke about the words that Filipinos mispronounce or mix up, in what I'd always thought of as an affectionate way. Your post reminded me of how my mom and grandma would always say, "close the light". My brother, cousins and I will say it to each other sometimes as a family inside joke. I think on some level, my mom was probably self-conscious of her accent and of mixing up her words like that. She never told us directly and would laugh when we teased her but it's little things, like her joining Toastmasters at work, that make me think she was probably a little self-conscious of how she spoke. Your post makes me want to ask her now.

I love this! The connotations of language can be so complex. My boyfriend frequently imitates the Polish accent of his parents and relatives. It comes from the same instinct that all of us children have to imitate our parents, I think. But I too have noticed distinctions in why and how we imitate others. Perhaps to avoid crossing lines, we shouldn’t imitate at all. Then again, I think so much richness would be lost in the stories we tell about the lives we share together. It’s very complex!